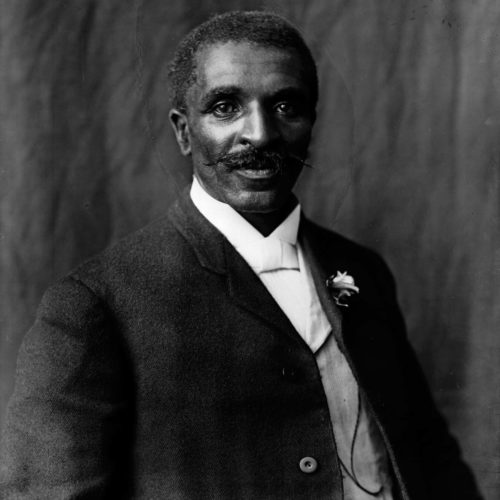

George Washington Carver was a scientist, inventor, agriculturalist, teacher, mentor, and without him life would be different. He discovered methods of soil improvement and taught them to poor southern farmers, helping plants to grow and life to flourish.

George Washington Carver is inspiring to me because he helped kids who were malnourished by teaching people how to plant their own food and how to help them grow faster.

George Washington Carver was born a slave near the end of the Civil War, around 1865. His father died in an accident before he was born, and his mother was kidnapped by one of the many bands of bushwhackers that were in Missouri at the time. A neighbor of the slave owner was hired to find him and his mom, but only succeeded in recovering George.

He was taken in by Moses and Susan Carver, where he learned how to cook, mend, do laundry, and embroider. As a result he also developed an interest in plants. At eleven years old, he traveled eight miles away to attend a school for people of color.

Carver eventually entered Simpson College, a small Methodist school in Indianola, Iowa. While at the College, he studied grammar, arithmetic, etymology, voice, and piano. He decided to stay on as a graduate student. He worked with L.H. Pammel, a mycologist, Carver honed his talent at identifying and treating plant diseases. Carver got a Master of Agriculture degree in 1896 and instantly got a lot of offers to teach at schools. He accepted a request to teach at Tuskegee Institute.

Carver fervently believed that his training as an agricultural scientist had prepared him for Tuskegee. But in reality Carver was not prepared for Tuskegee. He came from the North to teach “scientific agriculture” to southern farmers who believed they already knew how to farm.

Many on the faculty resented Carver’s exorbitant salary of $1,000 a year plus virtually all expenses for a man who did not have a family. At the time, the average salary for a Tuskegee faculty member was less than $400 a year.

Carver expected that as director of the newly created Agricultural Experimental Station he would devote most of his time to research. Booker T. Washington who had request him to teach there, was not hostile to research, but he also expected Carver to manage the school’s two farms, teach a full schedule of classes, serve on numerous committees (a chore Carver particularly disliked), and sit on the institute’s executive council as well as insure that the schools water closets and other sanitary facilities functioned properly.

He complained regularly about the classes but Washington did not give in. Washington’s successor, Robert Russa Moton, who took over in 1915, was more accommodating, relieving Carver of all teaching except summer school.

George Washington Carver believed he had a mission to use his training as an agricultural chemist to help improve the lot of poor black and white Southern farmers. He did this by teaching farmers about fertilization and crop rotation and by developing hundreds of new products from common agricultural products.

Later in his life Carver became very interested in chemurgy (“chem” from chemistry; “urgy”, Greek for work) movement. The term was used to describe scientists, agriculturalists, and industrialists who were determined to put chemistry to work to find nonfood uses for agricultural surpluses. Carver dedicated his entire scientific work to the goals later advocated by the chemurgy movement.

Carver’s laboratory at Tuskegee, almost from the beginning of his stay at the Institute, developed hundreds of new uses for agricultural products. The need for this resulted in part from Carver’s initial success in increasing agricultural productivity on the cotton-depleted, tired, old soils of the South. On the ten-acre experimental station at Tuskegee Carver was able, by using good farming practices and rotating soil-enriching plants like cowpeas and beans, to increase dramatically soil productivity.

Carver’s successes with planting legumes of course led to his encouraging Southern farmers to turn to these crops. This became even more urgent with the devastation in the early 20th century of the cotton crop due to the boll weevil. But if Southern farmers were to be convinced to grow crops other than cotton (or other traditional staples such as tobacco and rice), there had to be a market for peas, sweet potatoes, soybeans, and the like.

This need pushed Carver into the laboratory to work on finding alternative uses for these products. From sweet potatoes, for example, came a raft of new products: flours, starches, sugar, a faux coconut, vinegar, synthetic ginger, chocolate and such non-foods as stains, dyes, paints, writing ink, etc.

But it was the peanut which made Carver famous. The peanut attracted his attention because it is easy to grow, it enriches the soil, and it is a ready source of protein, an especially important consideration since poor black farmers could not afford meat. From the peanut Carver developed a host of new products: most notably milk, but also butter, meal, Worcestershire sauce, various punches, cooking oils, salad oil, milk and medicines as well as cosmetics such as hand lotions, face creams, and powder. All together, he discovered more than 300 food, industrial, and commercial products from the peanut.

Booker T. Washington, who was frequently at odds with Carver, never wavered in his belief that Carver’s “great forte is in teaching and lecturing. There are few people anywhere who have greater ability to inspire and instruct as a teacher…” Carver was not a great speaker. He had in fact a rather high-pitched voice. But he was a showman who frequently used dramatic examples and humor to make his points. Most importantly, his success as a teacher stemmed from his obvious enthusiasm for his subject, which was an appreciation of the wonders of nature. It did not matter whether the formal topic was chemistry, botany, or agriculture, for all of these subjects meant studying how to use nature for the benefit of man.

Carver died on January 5, 1943, at Tuskegee Institute after falling down the stairs of his home. He was 78 years old. Carver was buried next to Booker T. Washington on the Tuskegee Institute grounds.

Soon after, President Franklin D Roosevelt signed legislation for Carver to receive his own monument, an honor previously only granted to presidents George Washington and Abraham Lincoln. The George Washington Carver National Monument now stands in Diamond, Missouri. Carver was also posthumously inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame. I believe that without George Washington Carver we would live in a very different world.